90˚ The Margins as Center

Lynda Benglis, Robert Morris, Richard Serra, James Turrell

December 12, 2007 – January 24, 2008

Main Gallery

It is in its restriction, spatial limitations, and marginalization that the corner has come to serve as a significant site of creative production. It is the terminus of two walls and the site where floor and ceiling end. It is the furthest point from the center of a room and less brilliantly lit. It is a site of punishment and degradation. Of all the places in a gallery-the walls, the floor, the ceiling-it is perhaps the corner that is the most infrequently used and difficult place to anchor a work. The corner not only defies the flat plane of most painting and photography, but also reduces the workable space of a sculptural object from 360 degrees to just 90 degrees.

Reviewing the exhibition "Cornered" at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1995, which focused primarily on contemporary artists making work during the 1980s and 1990s, art historian Pepe Karmel traces the origins of setting sculpture in a corner to Vladimir Tatlin in 1915 with his work "Corner Relief." Although not cited by Karmel, it is important to note that Kazimir Malevich and Naum Gabo also began exploring the corner around this period with Malevich hanging his painting "Black Square," 1915 across a top corner space in the seminal 1915-16 exhibition "The Last Futurist Exhibition: 0, 10" in St. Petersburg, Russia. Working less architecturally, Naum Gabo created the space of a corner with his sculpture "Head of a Woman," 1917-20. Karmel further notes, that it was only "after a long hibernation" that corner sculptures began to reappear in the 1960s. In our own research we have found it remarkable to see the emergence of sculpture specifically sited in a corner being produced by so many artists from the 1960s such as Carl Andre, Lynda Benglis, Dan Flavin, Eva Hesse, Sol LeWitt, Bruce Nauman, Fred Sandback, Alan Saret, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, James Turrell, Richard Tuttle, and Lawrence Weiner. Also surprising has been the continued engagement with the corner by artists of later generations working across a spectrum of practices. To name just a few: Janine Antoni, Joseph Beuys, Gordon Matta-Clark, Rachel Whiteread, Joel Shapiro, Adrian Piper, Andre Cadere, Roni Horn, Kara Walker, Jim Hodges, Robert Gober, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Richard Artschwager, Gregor Schneider, and Gedi Sibony.

In thinking over the last several years about how best to contribute to this historically significant occurrence, we decided against an exhaustive survey. Similar to the brilliant strategies used by the works in this show-and works from the 1960s in general-we have chosen to overwhelm not by breadth but rather though significant and concisely chosen masterworks. To speak more about the selection process for this show, it is also interesting to note that as we narrowed our focus there were a number of directions this exhibition could have taken and while it became clear that we could have, for instance, created an entire exhibition strictly of triangular shapes in corners (with pieces by Benglis, Morris, Smithson, and Turrell, for example), we chose to mount an exhibition where each work engages the corner in its own unique and distinctive way. The specific artists included were chosen for their particular and ongoing fascination with the corner in the discourse of his or her work. As works from the 1960s have come to prove since, space is neither removed from ideology nor neutral. Space is forever and always endowed by judgments of value. By probing these notions of space, we can perhaps begin to explore the fallacies within a wider range of ideological constructs.

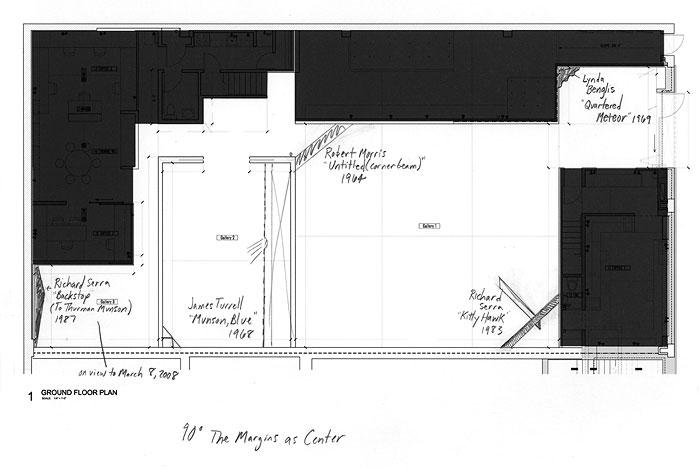

While not the central motivation of the exhibition, the five sculptures in 90° The Margins as Center: "Quartered Meteor," 1969 by Lynda Benglis, Robert Morris's "Untitled" (Corner Beam), 1964, Richard Serra's "Kitty Hawk," 1983 and "Backstop" (To Thurman Munson), 1987, and "Munson, Blue," 1968 by James Turrell, all engage the viewer with a sense of weight. Despite all of the works' intimations of physicality, what stands out is the variety of approaches used. In the tradition of the gallery's programming, having these historical shows has been a way to broaden both our understanding of contemporary art practices and a means to experience art and the world in a deeper way.

Through the selection of works, 90° The Margins as Center has chosen to emphasize the unique conditions and possibilities presented by our space and to interrogate notions of space. From the very front of the gallery to the furthest point back, works are being installed in places rarely, if ever used in the gallery's ten-year history at 24th Street. By focusing the visual incident into an often neglected destination, the works in 90° subtly undermine the determinations of importance imposed upon all physical spaces. Indeed, as the title of this show suggests, it is integral to this exhibition that the margins become focal points, not to rearrange a hierarchy, but rather, to create an equivalence of space.

Instead of finding in the corner a dead end, a place of entrapment, of enclosure, 90° The Margins as Center seeks to visit the corner as a charged space of production. From endings come beginnings-a place in which to find inspiration and to be inspired once again.

"I think it all has to do with going to extremes. I always enjoy extremes, I always like the fringes. Or you might call it, the margins."

-Felix Gonzalez-Torres

For more information and images please contact Jeremy Lawson at j.lawson@rosengallery.com or 212 627-6000